After lengthy deliberations, President Donald Trump has announced Kevin Warsh as his nominee to lead the Federal Reserve.

Trump has made it crystal clear that he wants a Fed chair who will lower interest rates aggressively, and signaled his confidence in Warsh in a statement, saying “he will never let you down.”

In particular, the president desires lower mortgage rates, seeing them as the only path to solve the housing crisis without reducing home values for current owners. Warsh has also spoken of the need for lower mortgage rates, but has a unique view on how to deliver them.

Warsh served as a Fed governor from 2006 to 2011, during the heart of the global financial crisis when he played a key role in shaping the central bank’s response to the meltdown.

But since leaving the Fed, he has become a sharp critic of Fed Chair Jerome Powell and the continuation of crisis-era Fed policies, arguing for an overhaul in approach that he calls “regime change.”

Although he never dissented publicly with policy decisions during his time at the Fed, Warsh was known as a “hawk” who tended to favor higher interest rates, a track record that would seem to put him at odds with Trump’s remit for easy money.

More recently though, Warsh has advocated for aggressive interest rate cuts, saying current policies are holding down economic growth and causing a housing recession, with first-time homebuyers struggling to afford a home.

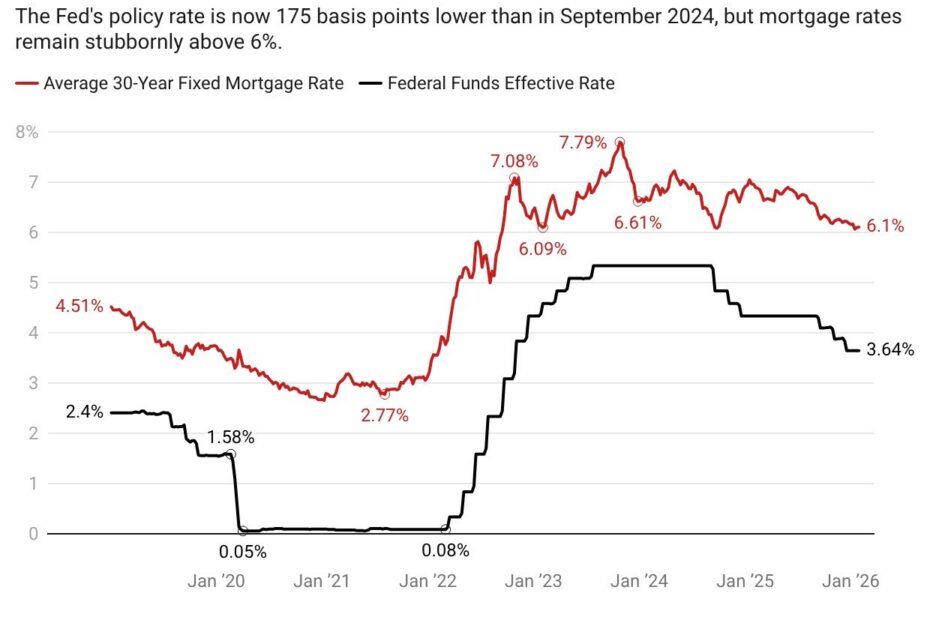

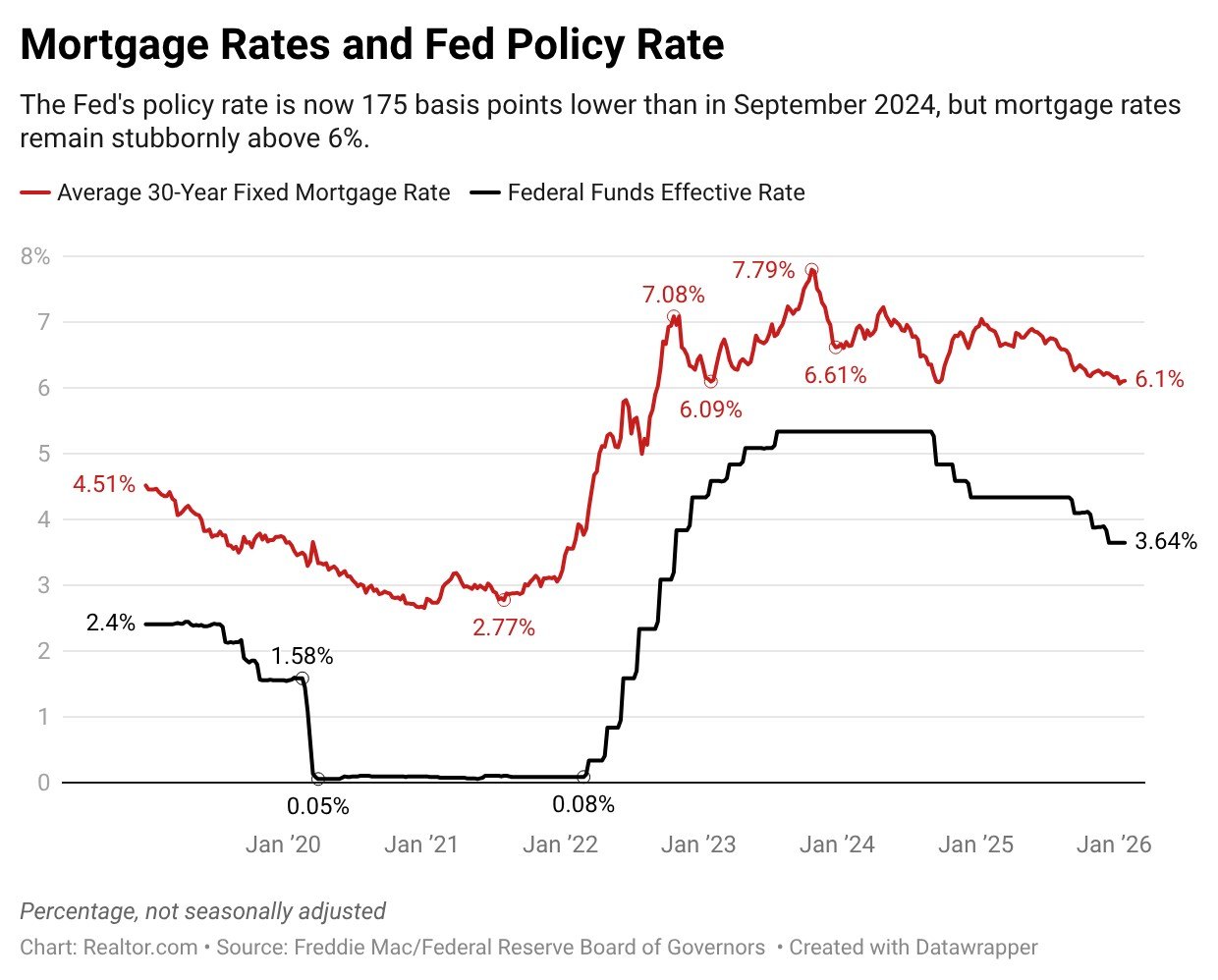

The Fed does not control mortgage rates, but rather sets the short-term rate for lending between commercial banks. Mortgage rates are determined in the free market, and influenced by investor expectations about inflation and Fed policy in the future.

The Fed uses higher interest rates to curb inflation, and lower rates to boost the labor market, in line with the central bank’s dual mandate of price stability and maximum employment.

But Warsh has said he believes current Fed policymakers misunderstand inflation, and have an untapped ability to lower short-term rates without igniting runaway price increases.

“They believe that inflation is driven by consumers, by wages that are rising too much, and consumers that are spending too much,” Warsh told Barron’s in a recent interview. “I fundamentally disagree. At the core, I think inflation comes about when the government spends too much and prints too much.”

Warsh says that by turning off what he calls the monetary “printing press,” or the Fed’s ability to increase the monetary supply by purchasing securities, “you have created space to lower interest rates.”

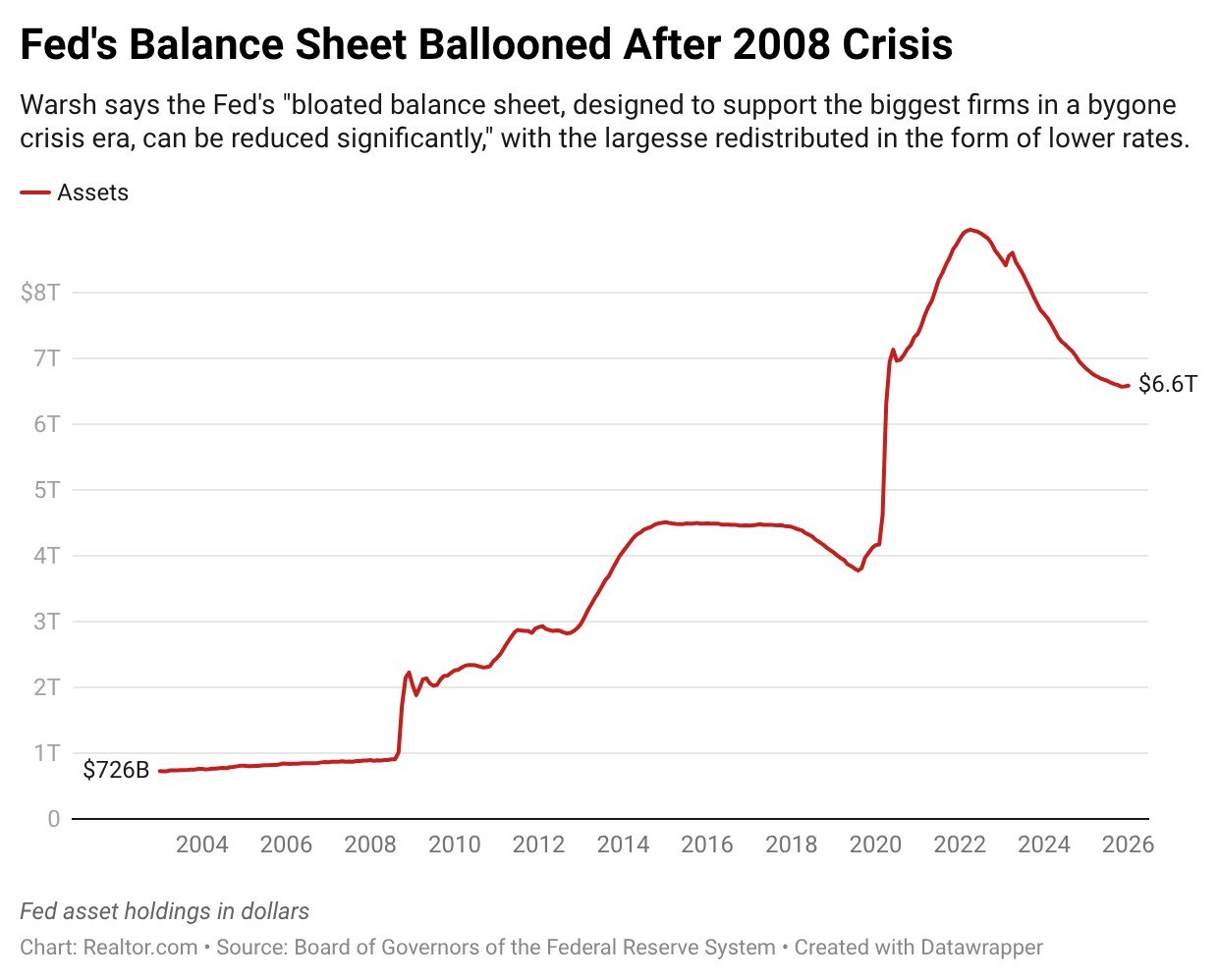

The key to unlocking lower rates, argues Warsh, is significantly reducing the Fed’s massive balance sheet, which stands at more than $6.6 trillion in Treasury notes and mortgage-backed securities.

“The Fed’s bloated balance sheet, designed to support the biggest firms in a bygone crisis era, can be reduced significantly,” Warsh wrote in a Wall Street Journal op-ed. “That largesse can be redeployed in the form of lower interest rates to support households and small and medium-size businesses.”

As part of the philosophy, Warsh has suggested he believes the Fed should sell off its $2 trillion hoard of mortgage-backed securities (MBS). However, there are reasons to believe that move would push mortgage rates higher, at least for a time.

The Fed went on an MBS buying spree during the COVID-19 pandemic as a measure to stabilize financial conditions, and some economists believe that move helped push mortgage rates down to record lows below 3%.

Some banking groups and bond experts have actually called on the Fed to buy more MBS as a measure to bring mortgage rates lower. However, from his comments, Warsh seems firmly opposed to that idea, and instead favors selling off the Fed’s remaining MBS holdings.

Warsh has also criticized the Fed’s use of forward guidance on interest rates—the “dot plot” of projections that emerged during the 2008 financial crisis.

“I think pre-committing as they do in these series of dots, each person saying how many times they cut … is deeply counterproductive,” Warsh told CNBC last year. “They’re taking a big risk with inflation.”

In effect, Warsh is opposed to the two primary tools the Fed has to interact with longer-term rates such as mortgages: the balance sheet and forward guidance.

However, he seems to believe a stripped down Fed that operates more like the central bank of pre-2008 will be able to transmit lower interest rates throughout the economy by squashing the monetary roots of inflation.

It’s an unorthodox view, and it’s unclear whether he will be able to convince the other 11 voting members of the Federal Open Market Committee, who have a equal say in policy. The panel voted Wednesday to leave interest rates unchanged at 3.5% to 3.75%, signaling skepticism of further rate cuts.

“This is not a crisis environment where the chair naturally accumulates outsized authority or a voting majority coalesces in line with the chair’s reading of the latest data,” says Realtor.com® senior economist Jake Krimmel. “If anything, it is an environment where building consensus is harder and where the new chair’s power is likely weaker, not stronger, than usual.”